The Gilded Age. The Victorian Era.The Second Industrial Revolution. The decade of the 1890s was a period of great wealth and prosperity for some, but a period of poverty and upheaval for others. The science fiction of the era was revolutionary, and set a precedent for what was to come in the succeeding centuries.

History:

The great struggle for the American continent continued with the Battle of Wounded Knee in 1890 between the Lakota tribe and the United States Cavalry. This was only one of the many continuing revolutions and internal conflicts that marked the decade.

The Panic of 1893 occurred in the United States after the railroad-based, overbuilt economy crashed. Yet, America still got involved in the war for independence in Cuba, leading to the Spanish-American war in 1898.

Some other notable events of the decade include the Klondike Gold Rush, and the commencement of the modern Olympic games.

Science:

[Still from Blacksmith Scene]

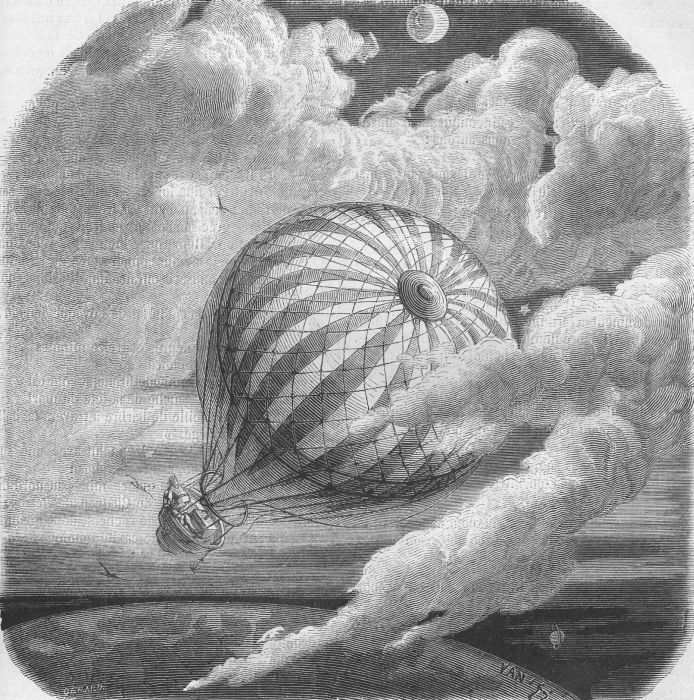

Inventors in the 1890s had a fixation with flight and travel. A notable milestone in flight history was the Derwitz Glider, a manned craft created and flown by Otto Lilienthal in 1891. The first commercial automobiles were produced by French company Panhard et Levassor in the same year.

Thomas Edison created the first motion picture device, the Kinetoscope, during 1893 and 1894. The first film, Blacksmith Scene, was shown at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences on May 9, 1893.

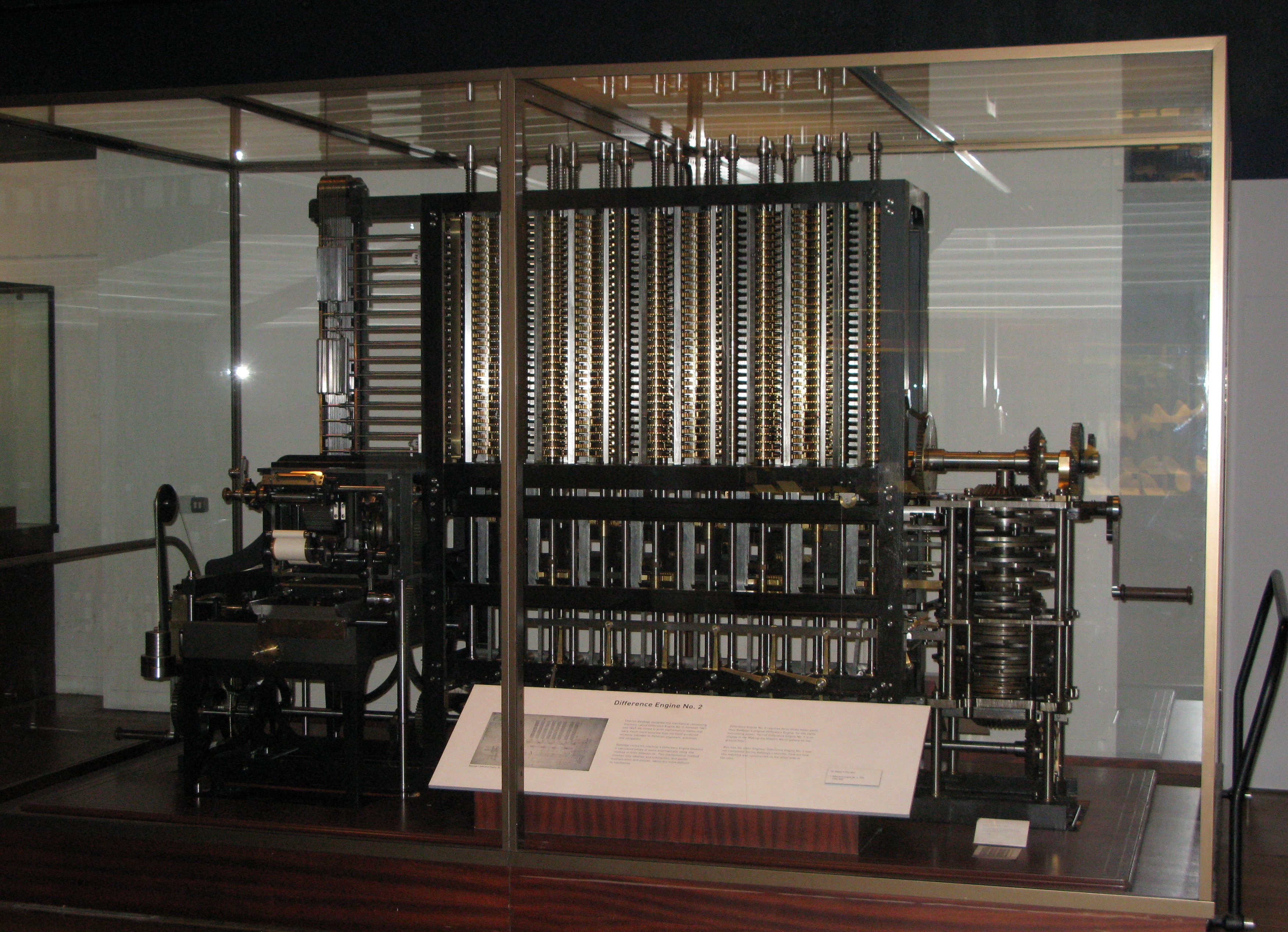

Several discoveries were made in the fields of chemistry and physics during the 1890s. Within one decade, the elements argon,neon, krypton, and xenon were discovered, as well as the X-ray.

Stories:

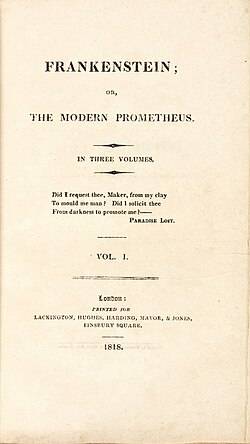

In 1890, William Morris wrote News From Nowhere, a romanticist, Marxist utopia story he used to defend socialism.

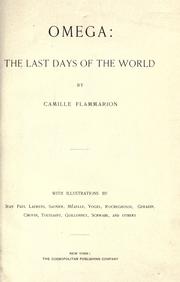

Author of the highly intellectual Lumen, Camille Flammarion published Omega: The Last Days of the World in 1894. It was about a comet made of Carbonic-oxide, which collided with earth in a fictional 25th century. The story was very philosophical, as was its predecessor, and contemplated the consequences of an apocalyptic catastrophe.

And then there was H.G. Wells. Considered by many to be the Father of Modern Science Fiction, Wells revolutionized the science fiction landscape by intelligently and skillfully exploring the concepts that would become staples of the genre in the century to come.

In 1895, Wells published The Time Machine, the story of one traveller’s magnificent voyage through the fourth dimension to the far future, and the dystopian posthuman society he finds there. 1896 saw the publication of Wells’ The Island of Dr. Moreau, in which a mad scientist attempts to create intelligent animals through bizarre and unethical experiments. Finally, in 1898, H.G. Wells wrote the quintessential alien invasion story, The War of the Worlds, a frightening disaster tale of survival in the midst of strange and unbeatable odds.

What better place to transition into the science fiction of the twentieth century than with the classic works of H.G. Wells. As the century turned, science fiction reached a turning point as a genre.

Keep on glowing in the dark,

Elora