(Samuel Morse's telegraph)

As in the 1820s and 30s, revolution spread rapidly across the globe. However, these revolutions were not only political, they were also philosophical, social, and technological. As the consequences of new ideas began to infiltrate everyday life, both science and fiction served as a sort of mirror, showing people the darker sides of human nature.

History:

Around 1848, violent revolutions in Europe caused mass migrations into America. Immigrants sought opportunity to advance their standing in life under the banner of freedom and democracy. Meanwhile, back in the old world, radical ideas were causing great unrest and violence. In 1849, a group of radical Russian intellectuals, including author Fyodor Dostoevsky, were arrested and sentenced to death for treason. They were brought before a firing squad, but at the last minute, their sentence was changed, and they were exiled to Siberia.

Science:

(Louis Agassiz)

In 1840, acclaimed natural scientist Louis Agassiz was the first to propose an ice age in earth’s past. 1944 saw the first usage of Morse’s telegraph. This was when he sent his famous Biblical message, “What hath God wrought”, (which comes from Numbers 23:23). In 1847, photography was first used in war, giving civilians a grisly look into the horrors of the Mexican-American war.

Stories:

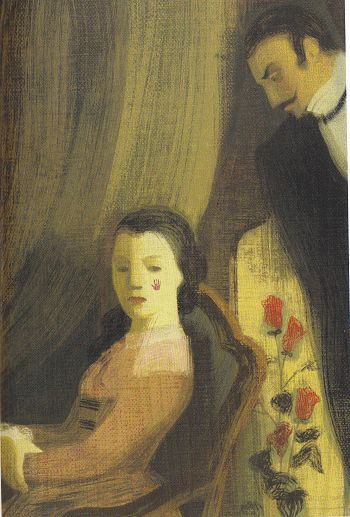

Edgar Allan Poe was still a very influential romanticist author in the 1840s, and wrote several proto-science fiction/horror stories. One of these is the grisly tale “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar”. This tells the story of a hypnotist who puts someone into a hypnotic trance just before he dies. It seems to be a precursor to many cryogenic suspension stories, and explores themes of life, death, and the attempted perpetuation of life.

James Fenimore Cooper, the American romanticist of The Last of The Mohicans fame, delved into the newborn science fiction genre with his novel The Crater, in which shipwrecked sailors discover a civilization in a crater on an island previously unknown to the outside.

Yet another romanticist, Nathaniel Hawthorne, wrote a short mad-scientist story, which explored man’s obsession with physical appearance.

Worldview:

If you couldn’t tell, most of the sci-fi of the 1840s came from the worldview of Romanticism. However, during this decade, a new philosophy was devised that would completely change the landscape of society in the middle of the 20th century.

In 1848, the German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels created the Communist Manifesto, which outlined their ideas of a perfect society, based on a completely equal society, and a complete rejection of any religion but atheism.

Science was changing. Philosophy was changing. The world was changing. In this time of upheaval and chaos, science fiction writers were still asking questions basic to humanity: how can we prevent death? What happens when we tamper with the human body? What is out there beyond the world that we know?

Keep on glowing in the dark,

Elora