If you hadn’t guessed already, I have a special fondness in my heart for good fictional characters. Though sci-fi historically has been a genre more of speculation than of character arcs, the best science fiction stories have been able to develop their ideas as well as their protagonists, antagonists, and side characters. I just discussed one of the most iconic characters in all of science fiction on Saturday, but today we are going to take a look at the characters who connected readers to the earliest science fiction stories.

Let’s get to it!

5. Hank Morgan (A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court by Mark Twain)-

An early adventurer through time, Hank Morgan, the titular Connecticut Yankee, bumbles his way through the past, trying to conform the Medieval world to his own standards of civilization. As bad as that sounds, how many of us wouldn’t do the same under similar circumstances?

4. The Time Machine/The Time Traveller (The Time Machine by H.G. Wells)-

Can a time machine be a character? Just take the issue up with your local Doctor Who fan, and I think you’ll be convinced. The Victorian sensibilities and personality of the title character of this book has sparked many an imagination, and inspired many an imitator, especially after it was brought to the silver screen in the 1960s adaptation of Wells’ classic. However, the adventurous protagonist, The Time Traveller, provides the heart of the story and the machine, and evokes a sense of wanderlust for other times in readers.

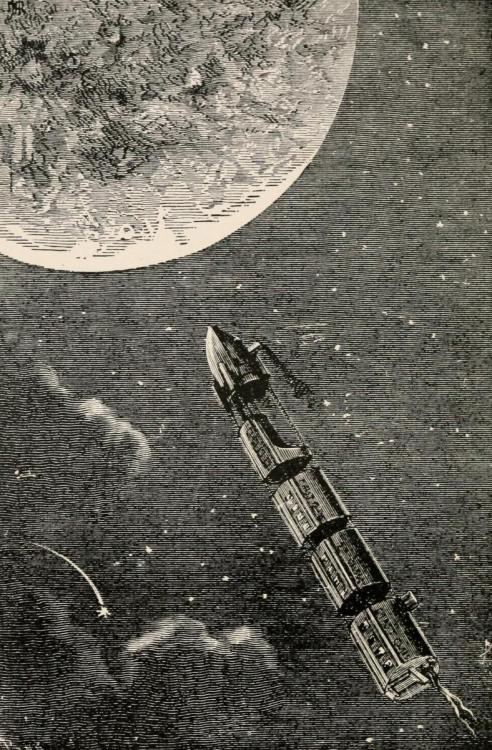

3. Captain Nemo (Twenty-Thousand Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne)-

This Indian prince turned mad inventor is the early science fiction equivalent of Captain Ahab from Moby Dick. However, this crazed captain’s vengeful intentions are turned toward the British Empire rather than a white whale. With a thirst for revenge, and remorse over the deaths of his crew, Captain Nemo set a precedent for many a great antihero.

2. Frankenstein and His Monster (Frankenstein by Mary Shelley)-

A classic example of confused name, the sympathetic creation in Mary Shelley’s classic is often tagged with the name of his creator, and when mad scientist Victor is mentioned, images of his monster. Both the tormented young scientist, and his forsaken creature, however, are well-developed characters who earn the investment readers put into their story.

1. Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde (The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson)-

Jekyll/Hyde is a classic and fascinating dichotomization of human nature. Good vs. evil, power vs. weakness, cruelty vs. compassion- these are all things we are forced to wrestle with. Robert Louis Stevenson presents this struggle in a literal way through a character/characters we simultaneously root for and despise.

What do you think? Who else belongs on this list? What are your favorite early sci-fi characters. I’d love to hear from you in the comments! Thanks for reading!

Keep on glowing in the dark,

Elora